Notes on Quotes

Martha Rosler • 1982

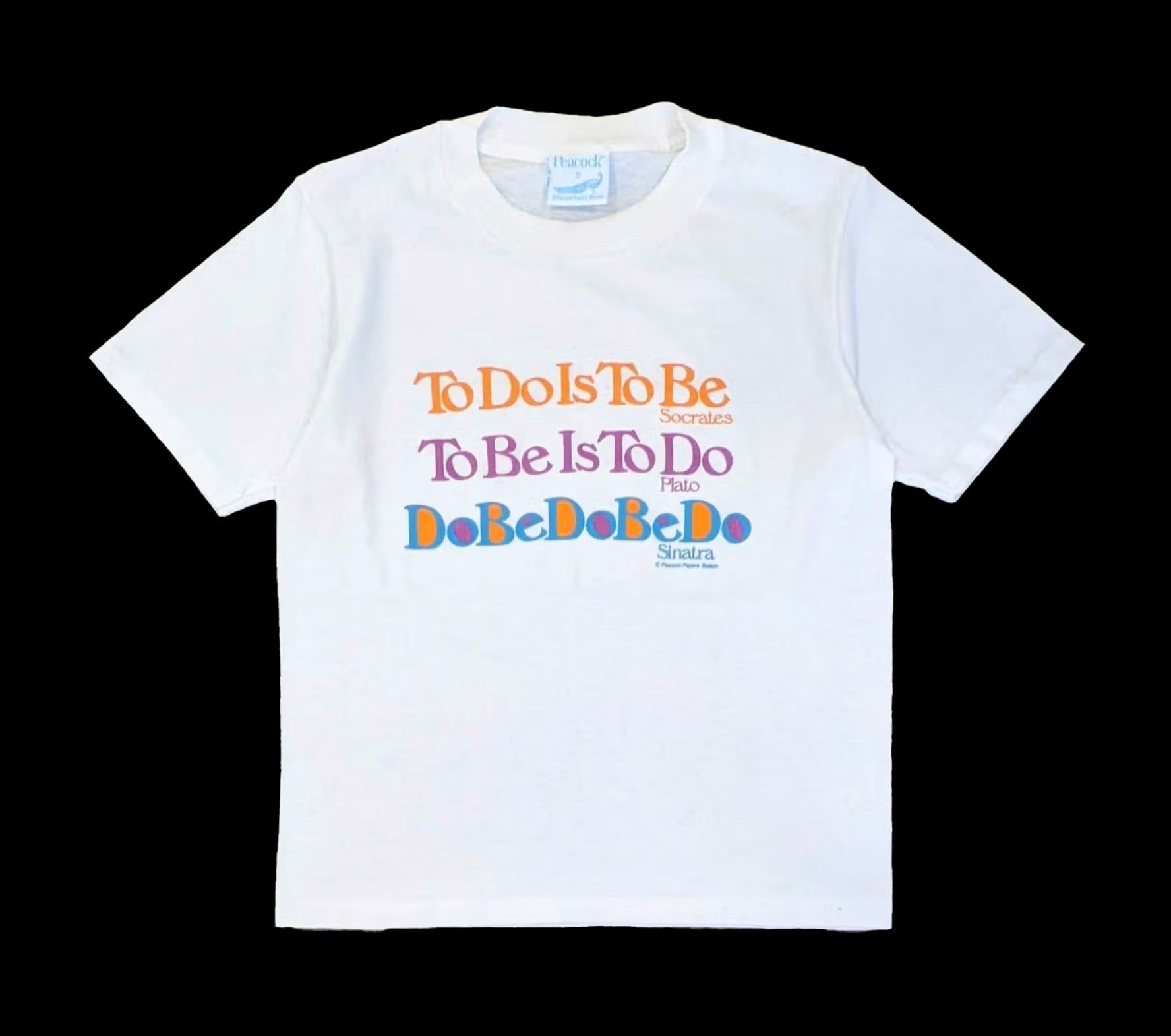

A Quotation, often as collage, B threads through twentieth-century art and literature fugally entwined with the countertheme of “originality.” In quotation the relation of quoter to quote, and to its source, is not open-and-shut. Quoting allows for a separation between quoter and quotation that calls attention to expression as garment and invites judgment of its cut . . . . Or, conversely, it holds out a seamless cloak of univocal authoritativeness for citers C to hide behind. D

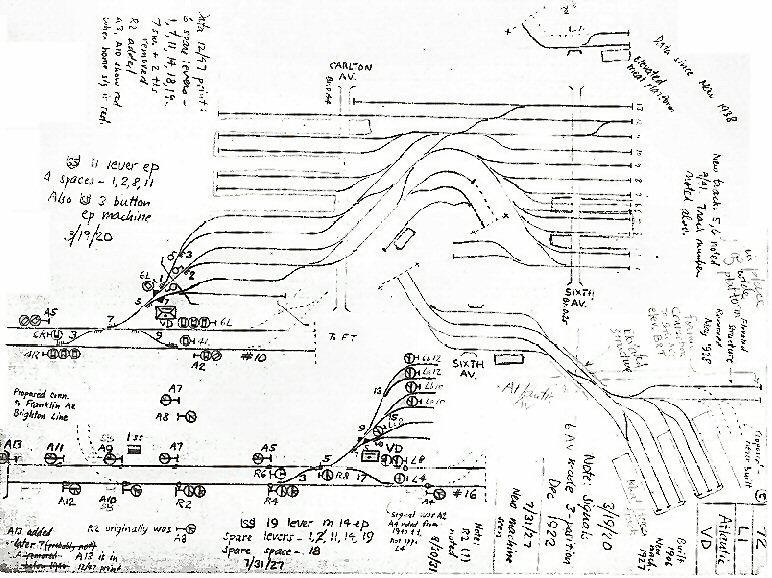

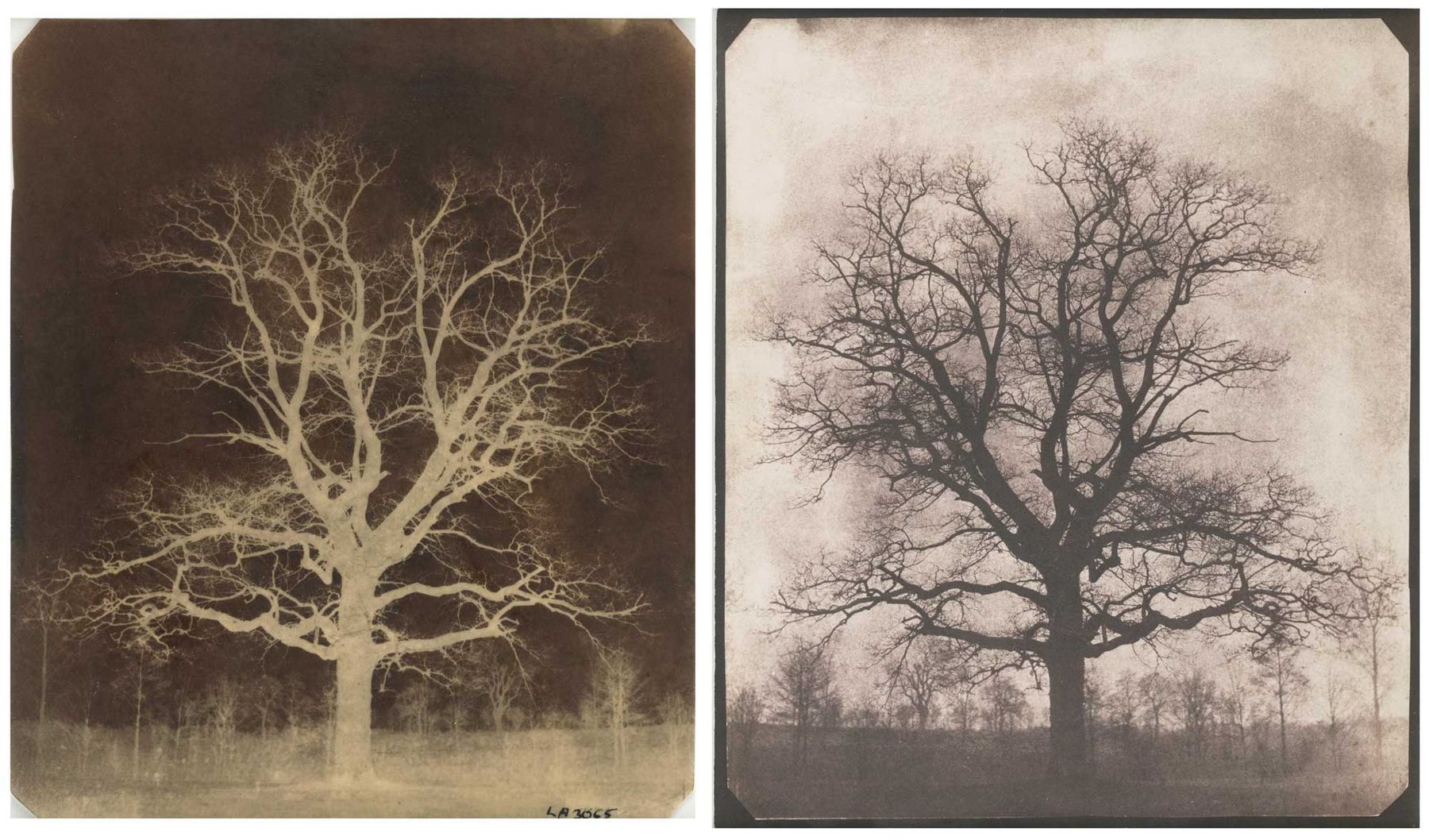

Although there is nothing unprejudiced about any representation, in the modern era attempts at a necessarily false “objectivity” in relation to meaning have periodically been made – whether in art, as in the German Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) or in journalism, United States style. Photography, dressed as science, has eased the path of this feigned innocence, for only photography might be taken as directly impressed by, literally formed by, its source.

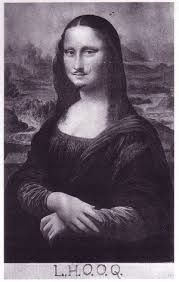

Because of the power and pervasiveness of the social myth of photographic literalism, there has been a great deal of energy devoted to the demolition of that myth of directness. G At various times the aim has been to invest the image with marks of authorship. Lately, the idea has been to expose the social H – that is, the ideological thrust I of the myth, its not-accidental character.

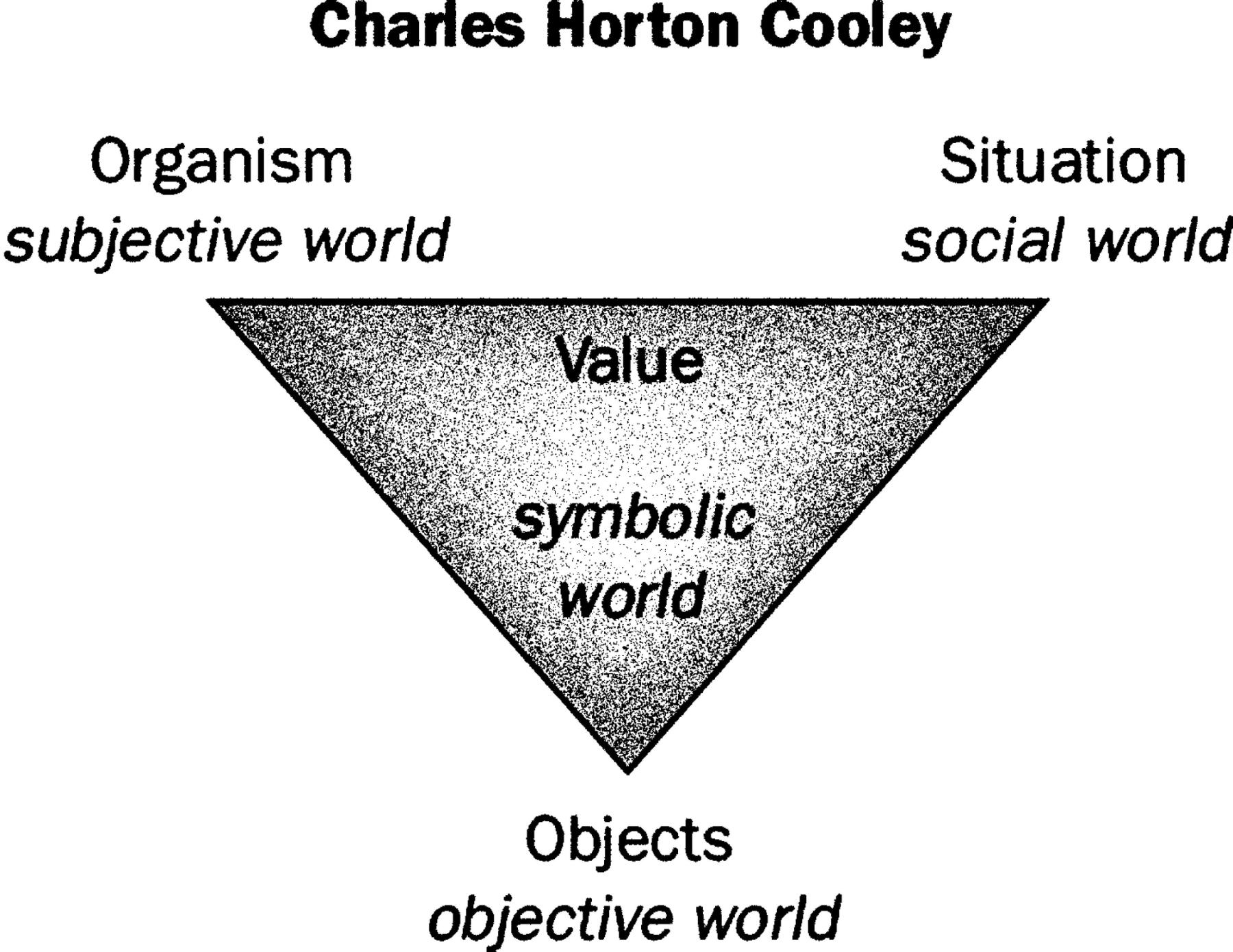

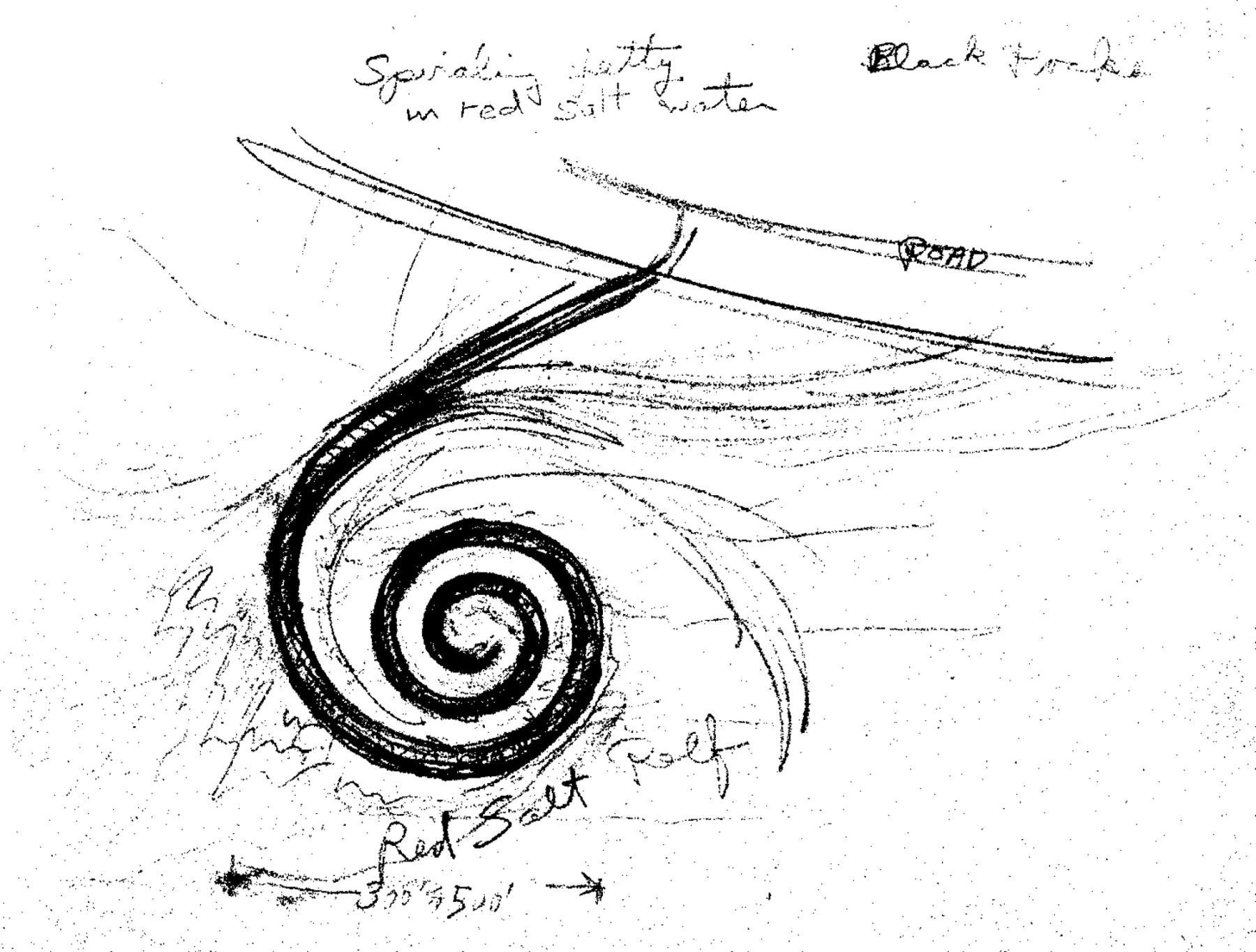

Quotation has mediation J as its essence, if not its primary concern, and any claims for objectivity or accuracy are made in relation to representations of representations, not representations of truth. The effect of this has tended to be a closure at the level of representation, which substantially leaves aside the investigation of power relations and their agencies.

But beyond the all-too-possible reductive-formalist or academic closure, in its straining of the relation between meaning and utterance, quotation can be understood as confessional, betraying an anxiety about meaning in the face of the living world, a faltered confidence in straightforward expression. At its least noble it is the skewering of the romantic consciousness on the reflexive realization of the impossibility of interpretational adequacy followed by a withdrawal into a paranoic pout.

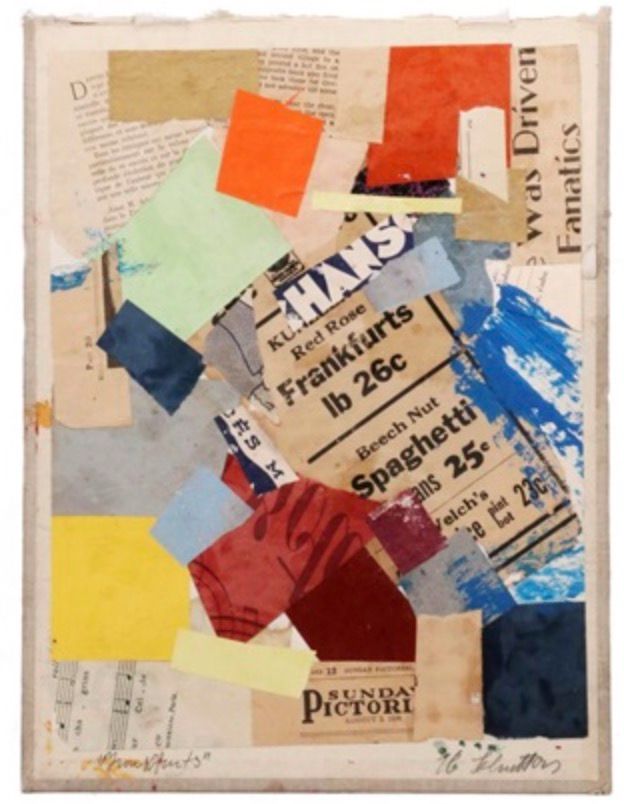

Pointing to the existence of a received system of meaning, a defining practice, quotation can reveal the thoroughly social nature of our lives. In a society in which personal relations are characterized by fragmentation while the trend of history is toward reorganization into a new, oppressive totality in which ideological controls may be decisive, quotation’s immanent self-consciousness about the avenues of ideological legitimation those of the State and its dominating class and culture or, more weakly, about routes of commercial utterance K, can accomplish the simple but incessantly necessary act of making the normal strange, the invisible an object of scrutiny, the trivial a measure of social life. In its seeming parasitism, quotation represents a refusal of socially integrated, therefore complicit, creativity. L

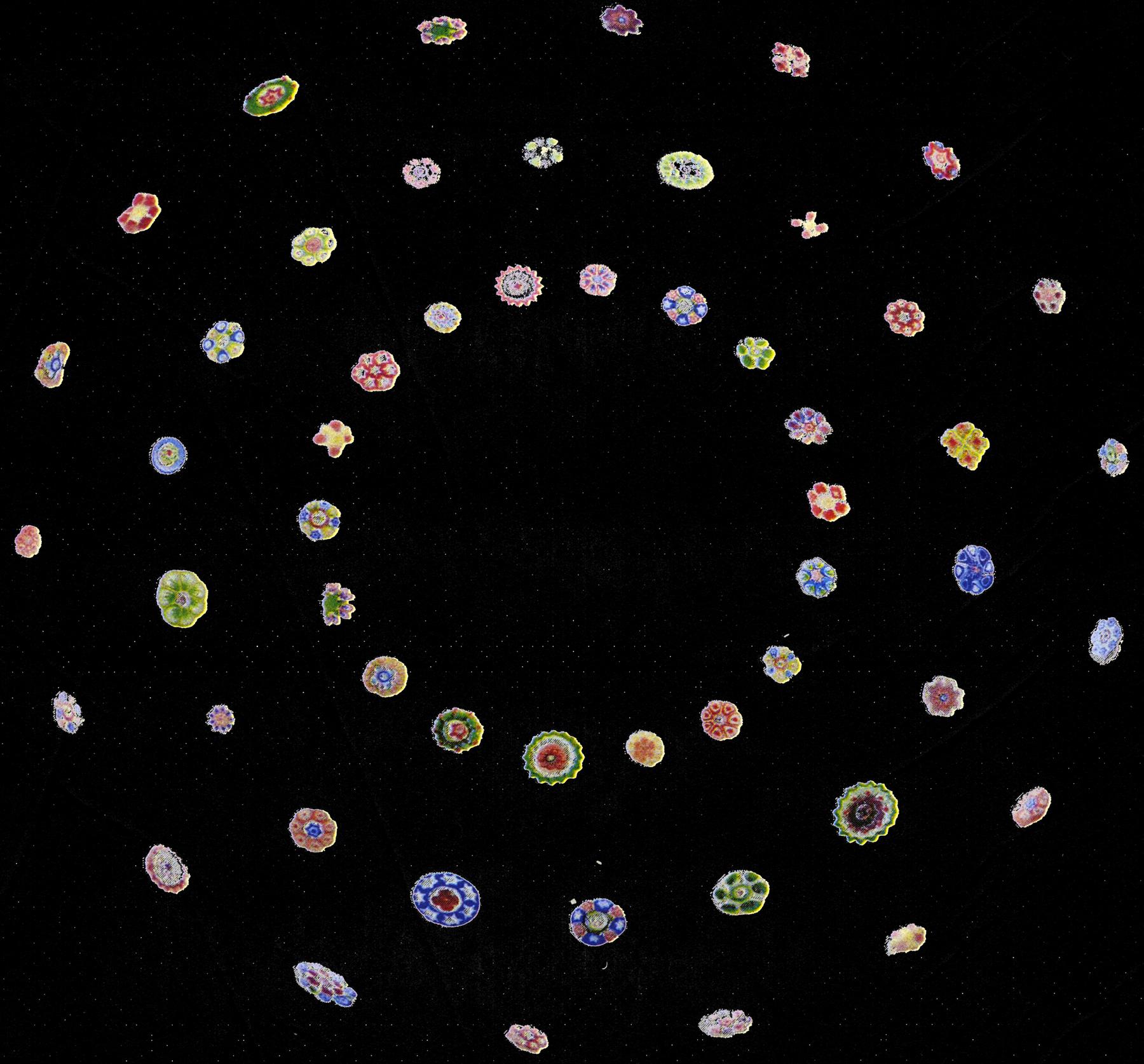

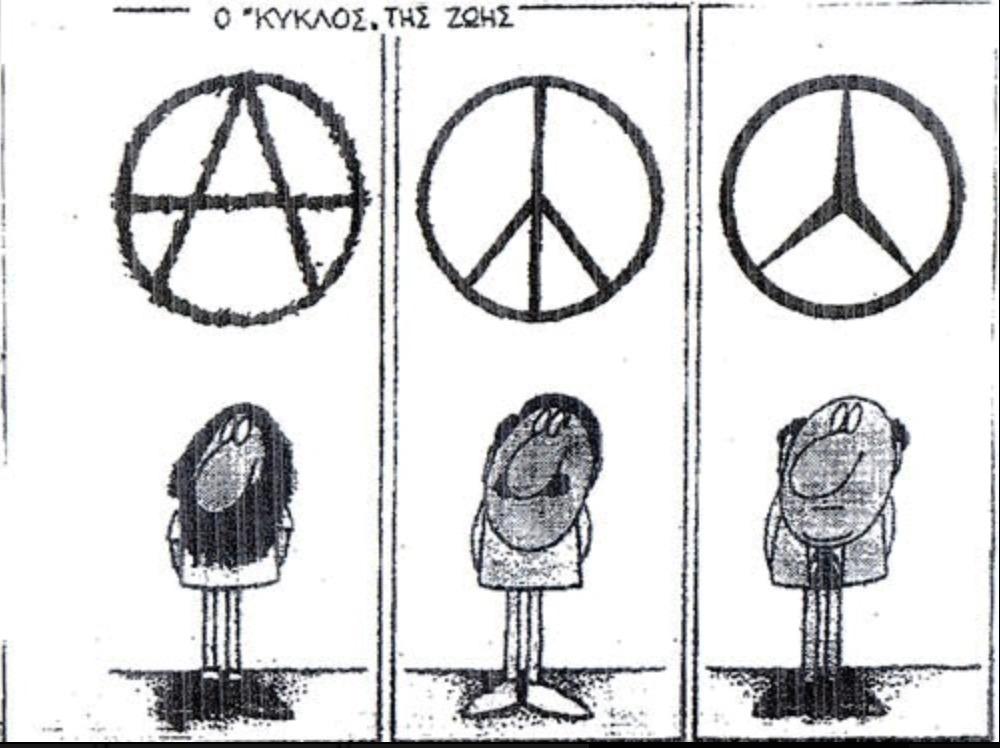

In this aspect, quotation is alienated sensibility. At certain historical junctures, quotation allows a defeat of alienation (alienation as psychological state, not as a structural disconnection of human beings and their labor power as described by Marx and Lukács), an asserted reconnection with obscured traditions. Yet the revelation of an unknown or disused past tradition emphasizes rupture M, with the present and the immediate past, a revolutionary break in the supposed stream of history. N, O

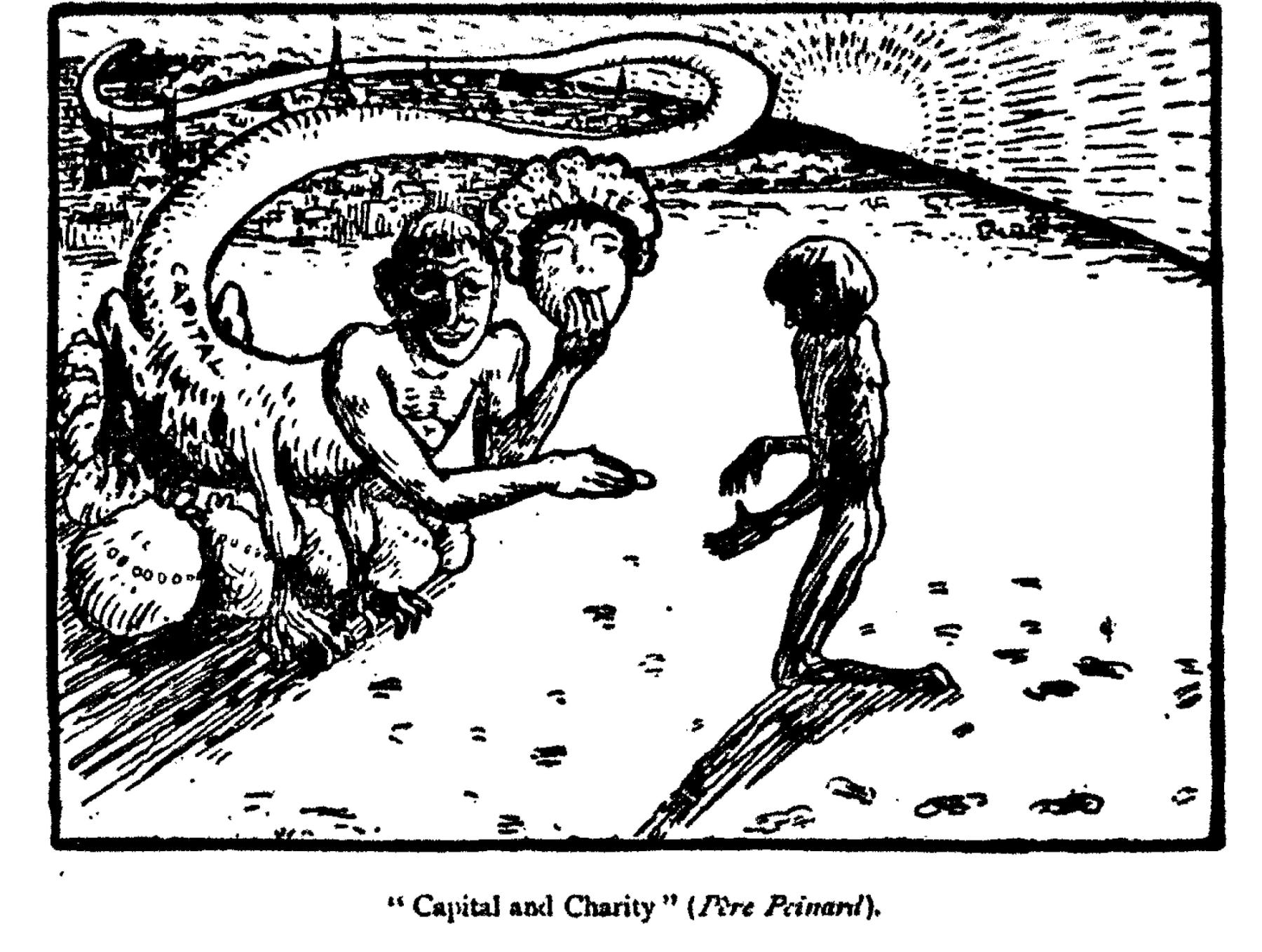

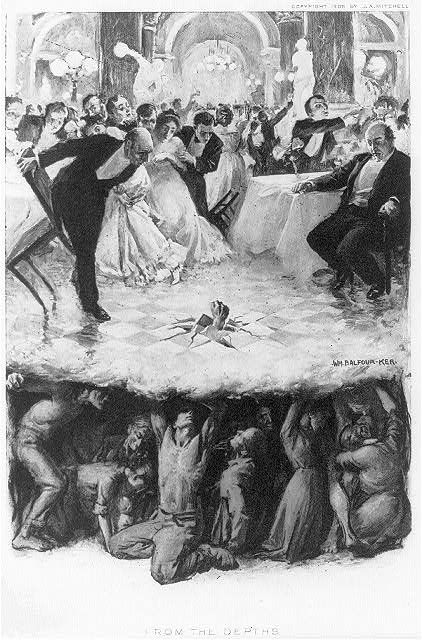

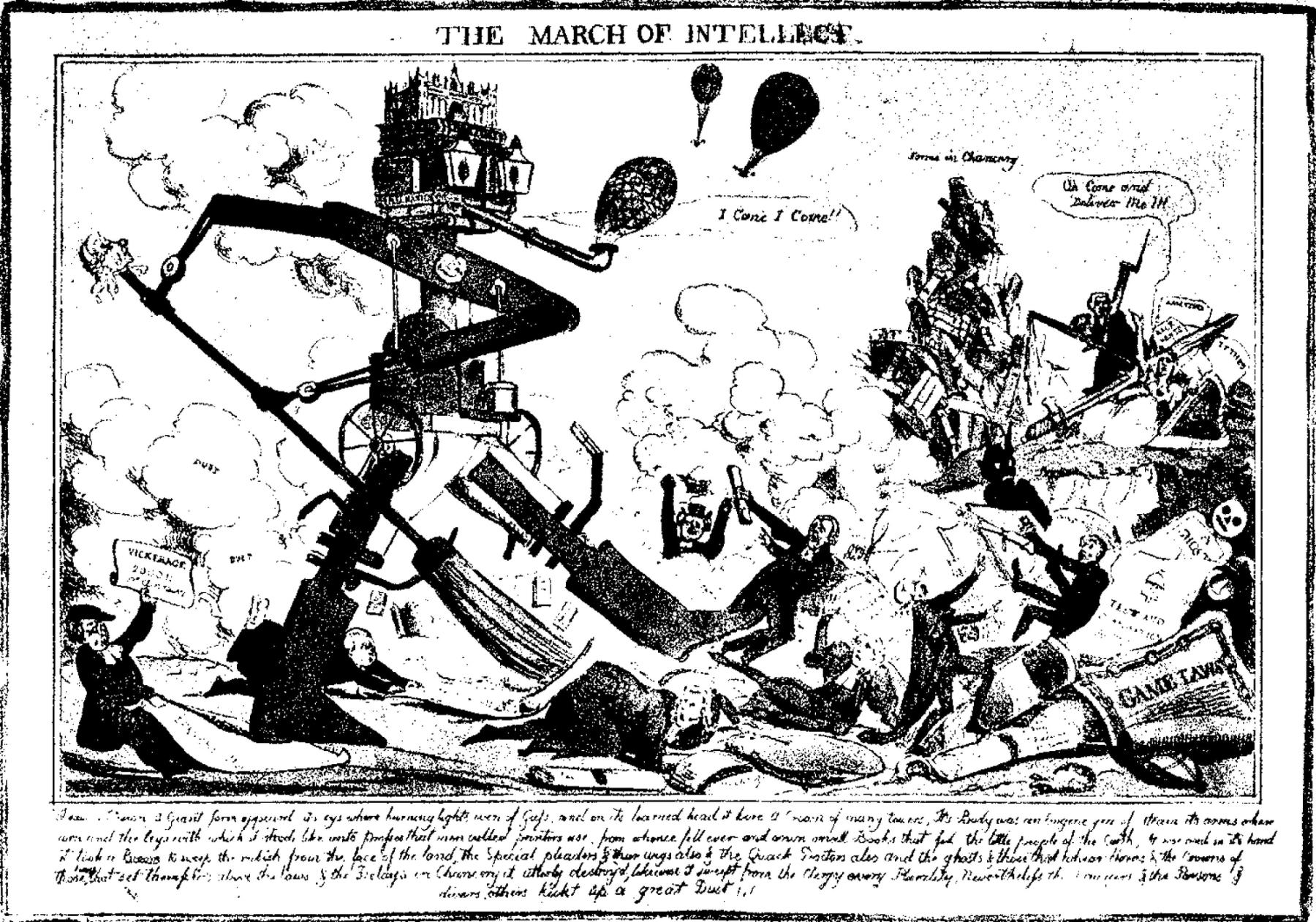

The writing of history is always controlled by the dominant class Q, which selects and interprets events according to its own successes and which sees history’s goal, its telos, as the triumph of that class. This use of quotation, that is, the appropriation of elements from the dustbin of official historiography, is intended to destroy the credibility of those reigning historical accounts in favor of the point of view of that history’s designated losers. R The homage of quotation is capable of signaling not self-effacement but rather a strengthening or consolidating resolve. Thus, for feminists in the past decade the resuscitation of a great variety of earlier works in all cultural fields was accompanied by energetic new production. The interpretation of the meaning and social origins and rootedness of those forms helped undermine the modernist tenet of the separateness of the aesthetic from the rest of human life, and an analysis of the oppressiveness of the seemingly unmotivated forms of high culture was companion to this work. The new historiographic championing of forgotten or disparaged works served as emblem of the countering nature of the new approach. That is, it served as an anti-orthodoxy announcing the necessity of the constant reinterpretation of the origin and meaning of cultural forms and as a specifically anti-authoritarian move.

Not incidentally, this reworking of older forms makes plain the essential interpenetration of “form” and “content.” T Yet bourgeois culture surrounds its opposition and, after initial rejection, assimilates new forms, first as a parallel track and then as an incorporated, perhaps minor, strand of the mainstream. U V In assimilating the old forms now refurbished, the ideological myths of the conditions of cultural production and the character of its creators are reimposed W and substituted for the unassimilable sections of the newly rewritten histories that rejected or denied the bourgeois paradigms of cultural production. X Today, we are witnessing the latter part of this process, in which critical and divergent elements in art are accepted but at the expense of the challenge to the paradigms of production or even, increasingly, at the expense of the challenge to institutionalized art-world power. Most particularly, there seems to be little challenge remaining to conventional notions of “success.”