The Tragedy of Irresponsibility

C. Wright Mills • 1944

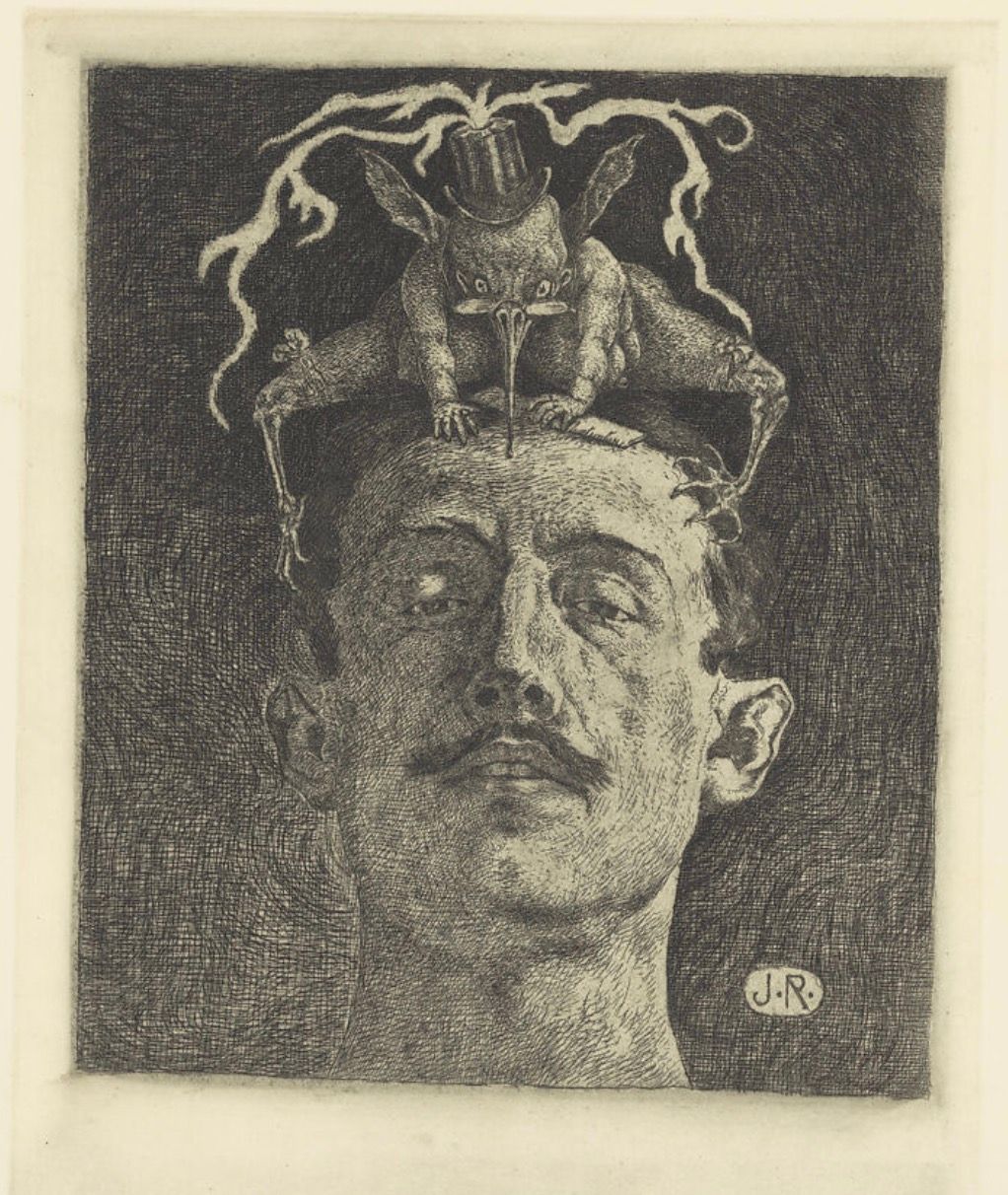

A We continue to know more and more about modern society, but we find the centers of political initiative less and less accessible. This generates a personal malady B that is particularly acute in the intellectual who has labored under the illusion that his thinking makes a difference. In the world of today the more his knowledge of affairs grows, the less effective the impact of his thinking seems to become. Since he grows more frustrated C as his knowledge increases, it seems that knowledge leads to powerlessness. He feels helpless in the fundamental sense that he cannot control what he is able to foresee. This is not only true of the consequences of his own attempts to act; it is true of the acts of powerful men whom he observes.

Such frustration arises, of course, only in the man who feels compelled to act. The “detached spectator” does not know his helplessness because he never tries to surmount it. E But the political man is always aware that while events are not in his hands he must bear their consequences. He finds it increasingly difficult even to express himself. If he states public issues as he sees them, he cannot take seriously the slogans and confusions used by parties with a chance to win power. He therefore feels politically irrelevant. Yet if he approaches public issues “realistically,” that is, in terms of the major parties, he has already so compromised their very statement that he is not able to sustain an enthusiasm for political action and thought. F

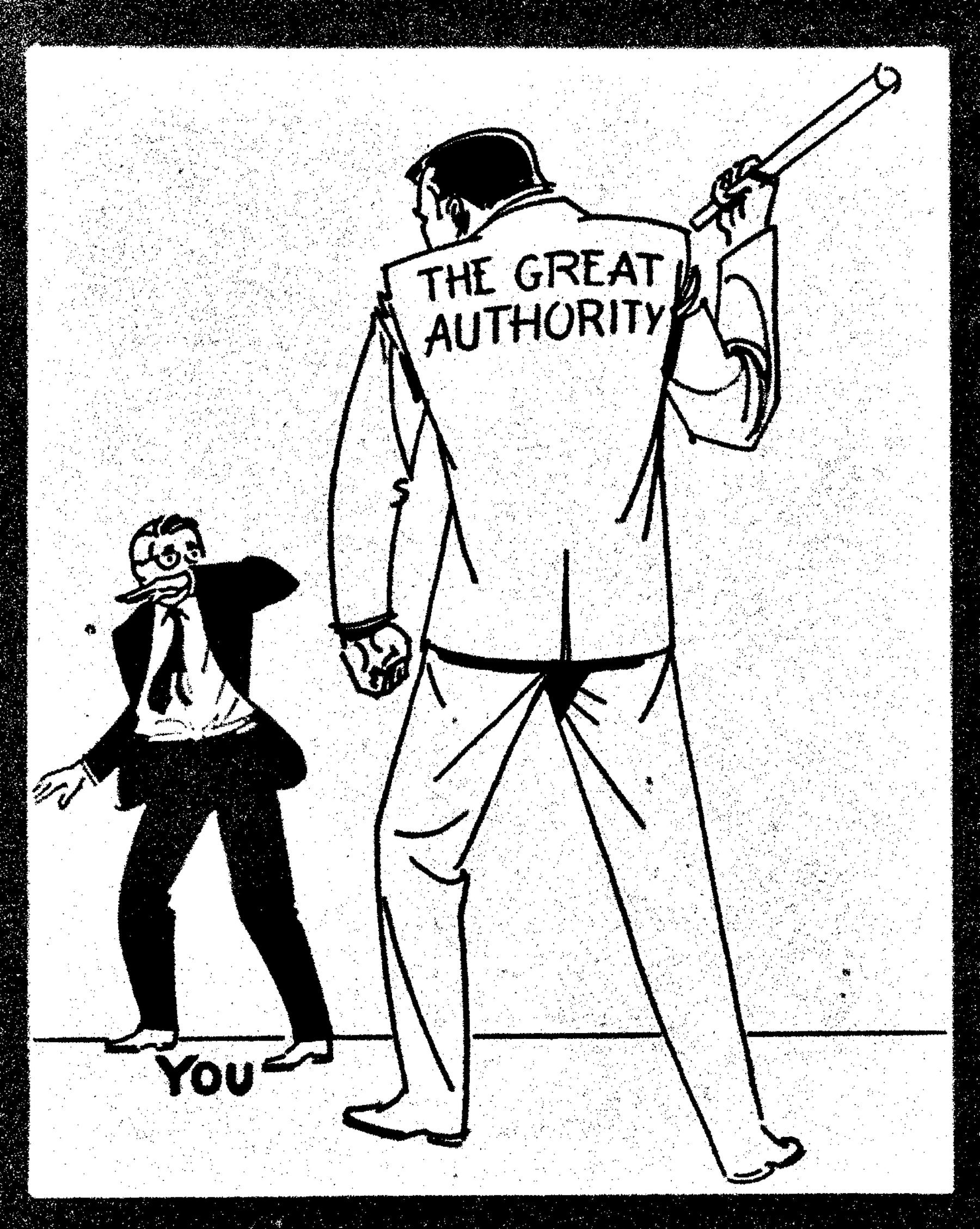

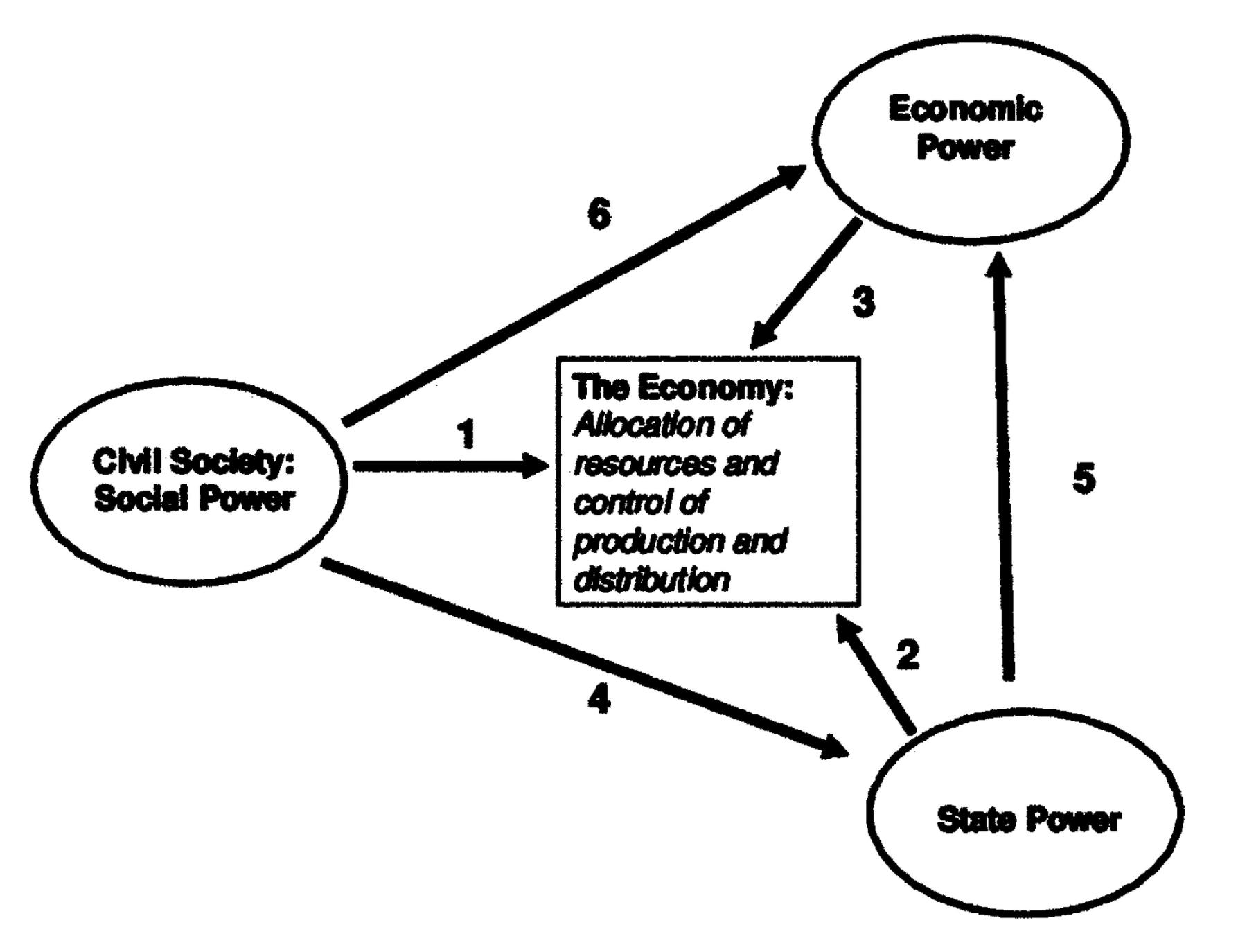

The political failure of nerve has a personal counterpart in the development of a tragic sense of life. H This sense of tragedy may be experienced as a personal discovery and a personal burden, but it is also a reflex of objective circumstances. It arises from the fact that at the centers of public decision there are powerful men who do not themselves suffer the violent results of their own decisions. I In a world of big organizations the lines between powerful decisions and grass-root democratic controls become blurred and tenuous, and seemingly irresponsible actions by individuals at the top are encouraged. The need for action prompts them to take decisions into their own hands, while the fact that they act as parts of large corporations or other organizations blurs the identification of personal responsibility. Their public views and political actions are, in this objective meaning of the word, irresponsible: the social corollary of their irresponsibility is the fact that others are dependent upon them and must suffer the consequences of their ignorance and mistakes, their self-deceptions, and their biased motives. The sense of tragedy in the intellectual who watches this scene J is a personal reaction to the politics and economics of irresponsibility.

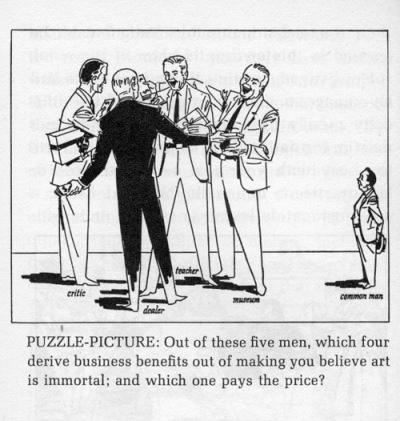

When irresponsible decisions prevail and values are not proportionately distributed, you will find universal deception K practiced by and for those who make the decisions and who have the most of what values there are to have. An increasing number of intellectually equipped men and women work within powerful bureaucracies and for the relatively few who do the deciding. L And if the intellectual is not directly hired by such organizations, then by little steps and in many self-deceptive ways he seeks to have his published opinions conform to the limits set by them and by those whom they do directly hire.

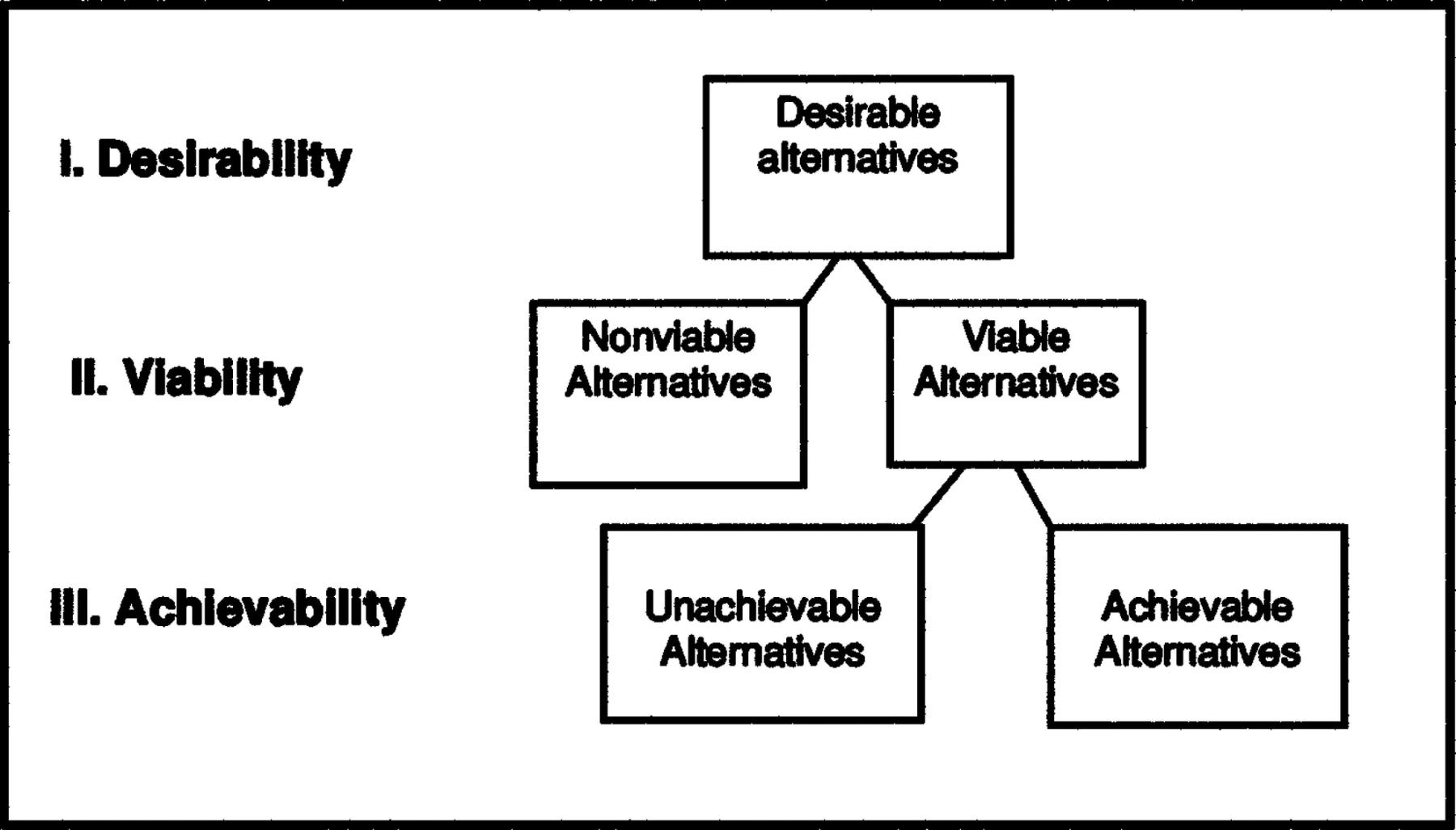

Any philosophy which is sensitive to the meaning of various societies for personal ways of life will give the idea of responsibility central place. That is why it is central in the ethics and politics of John Dewey and of the late German sociologist, Max Weber. The intellectual’s response to the tragic fact of irresponsibility has a wide range but we can understand it in terms of where the problem is faced. The tragedy of irresponsibility may be confronted introspectively, as a moral or intellectual problem. It may be confronted publicly, as a problem of the political economy.

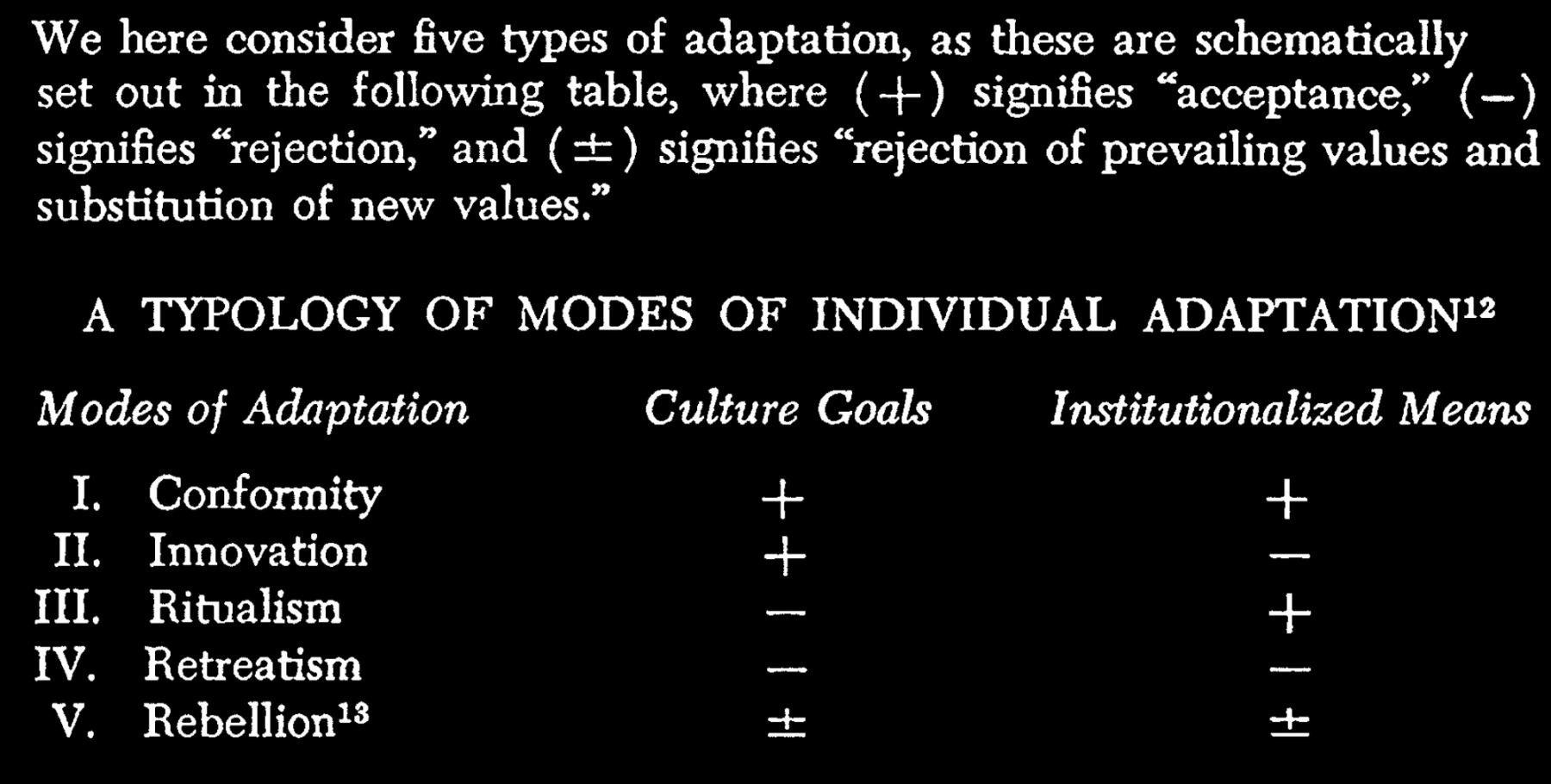

Along this scale there are (1) simple evaluations of our selves; (2) objective considerations of events; (3) estimates of our personal position in relation to the objective distribution of power and decision.

An adequate philosophy uses each of these three styles of reflection in thinking through any position that is taken.

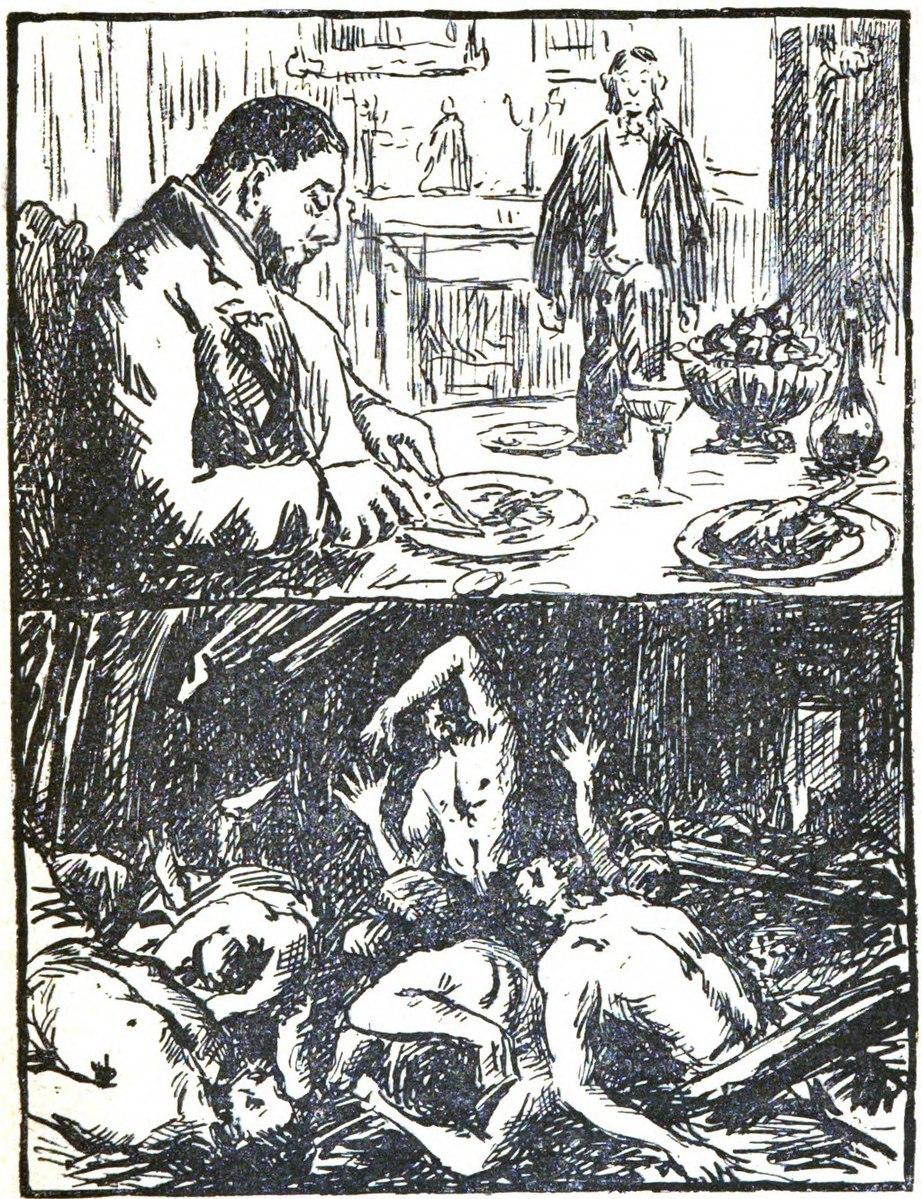

(1) If ethical and political problems are defined solely in terms of the way they affect the individual, he may enrich his experience, expand his sensitivities, and perhaps adjust to his own suffering N. But he will not solve the problems he is up against. He is not confronting them at their deeper sources.

(2) If only the objective trends of society are considered, personal biases and passions, inevitably involved in observation and thought of any consequence, are overlooked. Objectivity need not be an academic cult of the narrowed attention; it may be more ample and include meaning as well as “fact.” What many consider to be “objective” is only an unimaginative use of already plotted routines of research. This may satisfy those who are not interested in politics; it is inadequate as a full orientation. It is more like a specialized form of retreat than the intellectual orientation of a man.

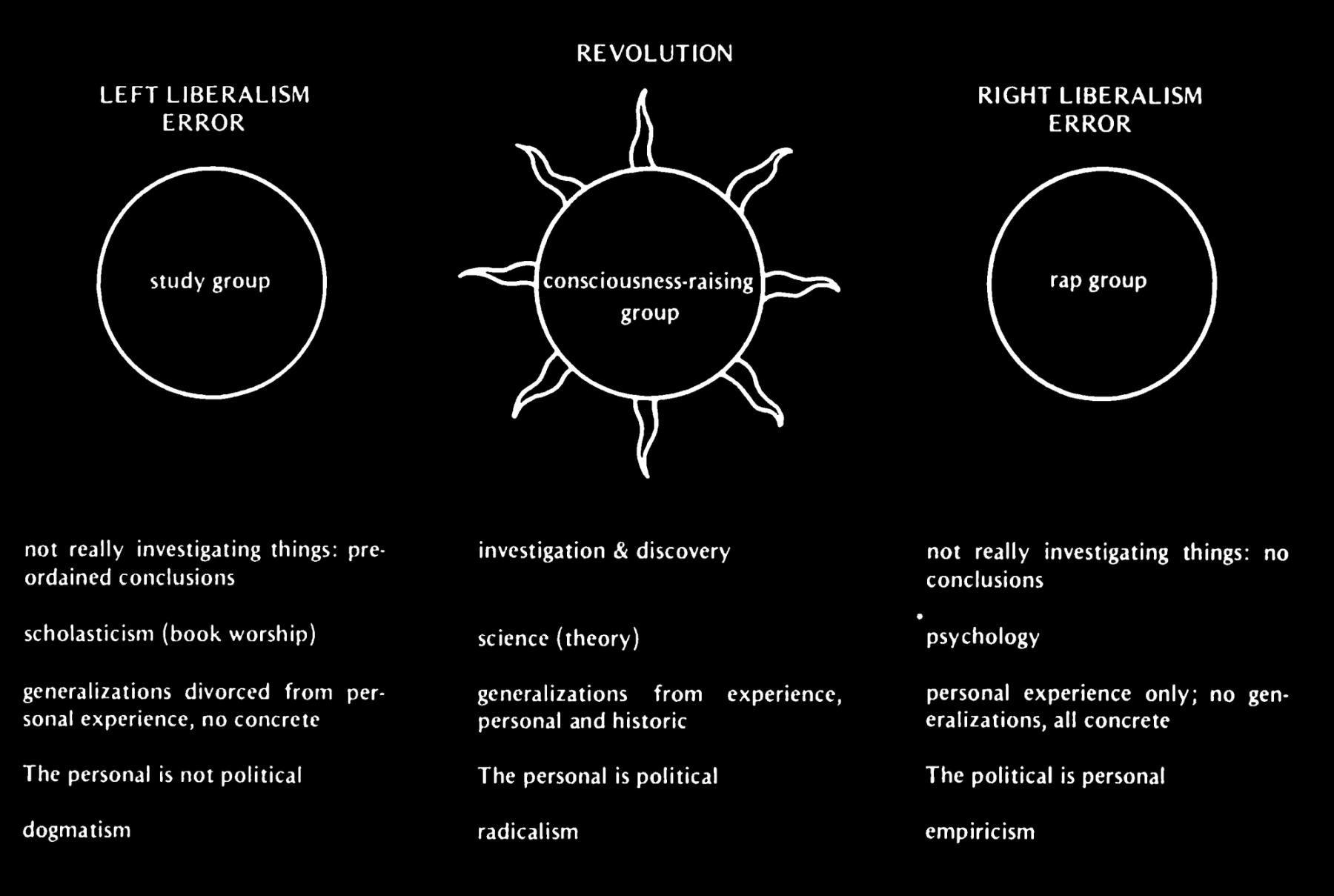

(3) The shaping of the society we shall live in and the manner in which we shall live in it are increasingly political. And this society includes the realms of intellect and of personal morals. O If we demand that these realms be geared to our activities which make a public difference, then personal morals and political interests become closely related; any philosophy that is not a personal escape involves taking a political stand. If this is true, it places great responsibility upon our political thinking. Because of the expanded reach of politics, it is our own personal style of life and reflection we are thinking about when we think about politics.

The independent artist P and intellectual are among the few remaining personalities equipped to resist and to fight the stereotyping and consequent death of genuinely lively things. Fresh perception now involves the capacity continually to unmask and to smash Q the stereotypes of vision and intellect with which modern communications swamp us. These worlds of mass-art and massthought are increasingly geared to the demands of politics R That is why it is in politics that intellectual solidarity and effort must be centered. If the thinker does not relate himself to the value of truth in political struggle, he cannot responsibly cope with the whole of live experience.